ARE THERE ANY FALLACIES

IN THE REASONING?

Thus far, you have been working at taking the raw materials a writer or speaker gives you and assembling them into a meaningful overall structure. You have learned ways to remove the irrelevant parts from your pan as well as how to discover the "invisible glue" that holds the relevant parts together—that is, the assumptions. All these things have been achieved by asking critical questions.

Let's briefly review these questions:

1. What are the issue and the conclusion?

2. What are the reasons?

3. What words or phrases are ambiguous?

4. What are the value conflicts and assumptions?

5. What are the descriptive assumptions?

Asking these questions should give you a clear understanding of the communicator's reasoning as well as a sense of where there might be strengths and weaknesses in the argument. Most remaining chapters focus on how well the structure holds up after being assembled. Your major question now is, "How acceptable is the conclusion in light of the reasons provided?" You are now ready to make your central focus evaluation. Remember: The objective of critical reading and listening is to judge the acceptability or worth of conclusions.

While answering our first five questions has been a necessary beginning to the evaluation process, we now move to questions requiring us to make judgments more directly and explicitly about the worth or the quality of the reasoning. Our task now is to separate the "Fools Gold" from the genuine gold.

We want to isolate the best reasons—those that we want to treat most seriously. Your first step at this stage of the evaluation process is to examine the reasoning structure to determine whether the communicator's reasoning has depended on false or highly doubtful assumptions or has "tricked" you through either a mistake in logic or other forms of deceptive reasoning. Chapter 6 focused on finding and then thinking about the quality of assumptions.

This chapter, on the other hand, highlights those reasoning "tricks" that others and we call fallacies.

Three common tricks are:

1. providing reasoning that requires erroneous or incorrect assumptions;

2. distracting us by making information seem relevant to the conclusion when it is not; and

3. providing support for the conclusion that depends on the conclusion's already being true.Spotting such tricks will prevent us from being unduly influenced by them. Let's see what a fallacy in reasoning looks like.

Dear editor,

I was shocked by your paper's support of Senator Spendall's arguments for a tax hike to increase state money available for improving highways. Of course the Senator favors such a hike. What else would you expect from a tax and spend liberal.

Note that the letter at first appears to be presenting a "reason" to dispute the tax-hike proposal, by citing the senator's liberal reputation. But the reason is not relevant to the conclusion. The question is whether the tax hike is a good idea. The letter writer has ignored the senator's reasons and has provided no specific reasons against the tax hike; instead, she has personally attacked the senator by labeling him a "tax and spend liberal." The writer has committed a fallacy in reasoning, because her argument requires an absurd assumption to

be relevant to the conclusion, and shifts attention from the argument to the arguer—Senator Spendall. An unsuspecting reader not alert to this fallacy may be tricked into thinking that the writer has provided a persuasive reason.

This chapter gives you practice in identifying such fallacies so that you will not fall for such tricks.

Critical Question: Are there any fallacies in the reasoning?

Attention: A fallacy is a reasoning "trick" that an author might use while trying to persuade you to accept a conclusion.

A Questioning Approach to Finding Reasoning Fallacies

There are numerous reasoning fallacies. And they can be organized in many different ways. Many are so common that they have been given formal names. You can find many lengthy lists of fallacies in numerous texts and Web sites.

Fortunately, you don't need to be aware of all the fallacies and their names to be able to locate them. If you ask yourself the right questions, you will be able to find reasoning fallacies—even if you can't name them. Thus, we have adopted the strategy of emphasizing self-questioning strategies, rather than asking you to memorize an extensive list of possible kinds of fallacies. We believe, however, that knowing the names of the most common fallacies can sensitize you to fallacies and also act as a language "short cut" in communicating your reaction to faulty reasoning to others familiar with the names. Thus, we provide you with the names of fallacies as we identify the deceptive reasoning processes and encourage you to learn the names of the common fallacies described on page 98 at the end of the chapter.

We have already introduced one common fallacy to you in our Dear Editor example above. We noted that the writer personally attacked Senator Spendall instead of responding directly to the senator's reasons. Seeing such an argument, the critical thinker should immediately ask, "But what about the arguments that Senator Spendall made?" The Dear Editor reasoning illustrates the Ad Hominem fallacy. The Latin phrase Ad Hominem means "against the man or against the person." There are a variety of ways of making irrelevant attacks against a person making a claim, the most common of which is attacking his character or shifting attention to his circumstances or interests. Arguing Ad Hominem is a fallacy because the character or interests of individuals making arguments usually are not relevant to the quality of the argument being made. It is attacking the messenger instead of addressing the message.

Here is another brief example of Ad Hominem reasoning.

Sandy: "I believe that joining sororities is a waste of time and money."

Julie: "Of course you would say that, you didn't get accepted by any sorority."

Sandy: "But what about the arguments I gave to support my position?"

Julie: "Those don't count. You're just a sore loser."

You can start your list of fallacy names with this one. Here is the definition:

________________________________________________________________________________

F: Ad hominem: An attack, or an insult, on the person, rather than directly addressingthe person's reasons

________________________________________________________________________________

Evaluating Assumptions as a Starting Point

If you have been able to locate assumptions (see Chapters 5 and 6), especially descriptive assumptions, you already possess a major skill in determining questionable assumptions and in finding fallacies. The more questionable the assumption, the less relevant the reasoning. Some "reasons," such as Ad

Hominem arguments, will be so irrelevant to the conclusion that you would have to supply blatantly erroneous assumptions to provide a logical link. Such reasoning is a fallacy, and you should immediately reject it. In the next section, we take you through some exercises in discovering other common fallacies. Once you know how to look, you will be able to find most fallacies. We suggest that you adopt the following thinking steps in locating fallacies:

- Identify the conclusions and reasons.

- Always keep the conclusion in mind and consider reasons that you think might be relevant to it; contrast these reasons with the author's reasons.

- If the conclusion supports an action, determine whether the reason states a specific and/or concrete dvantage or a disadvantage; if not, be wary!

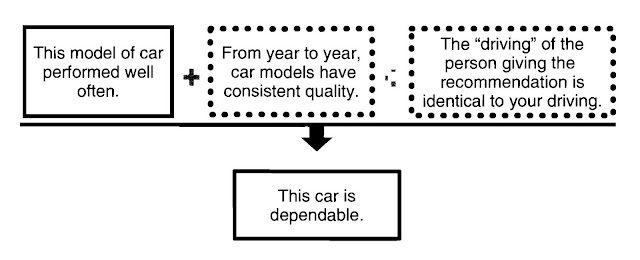

- Identify any necessary assumption by asking yourself, "If the reason were true, what would one have to believe for it to logically support the conclusion, and what does one have to believe for the reason to be true?"

- Ask yourself, "Do these assumptions make sense?" If an obviously false assumption is being made, you have found a fallacy in reasoning, and that reasoning can then be rejected.

- Check the possibility of being distracted from relevant reasons by phrases that strongly appeal to your emotions.

To demonstrate the process you should go through to evaluate assumptions and thus recognize many fallacies, we will examine the quality of the reasoning in the following passage. We will begin by assembling the structure.

The question involved in this legislation is not really a question of whether alcohol consumption is or is not detrimental to health. Rather, it is a question of whether Congress is willing to have the Federal

Communications Commission

make an arbitrary decision that prohibits alcohol advertising on radio and television. If we should permit the FCC to take this action in regard to alcohol, what is there to prevent it from deciding next year that candy is detrimental to the public health in that it causes obesity, tooth decay, and other health problems?

What about milk and eggs? Milk and eggs are high in saturated animal fat and no doubt increase the cholesterol in the bloodstream, believed by many heart specialists to be a contributing factor in heart disease. Do we want the FCC to be able to prohibit the advertising of milk, eggs, butter, and ice cream on TV?

Also, we all know that no action by the federal government, however drastic, can or will be effective in eliminating alcohol consumption completely. If people want to drink alcoholic beverages, they will find some way to do so.

CONCLUSION: The FCC should not prohibit alcohol advertising on radio and television.

REASONS:

- If we permit the FCC to prohibit advertising on radio and television, the FCC will soon prohibit many kinds of advertising, because many products present potential health hazards.

- No action by the federal government can or will be effective in eliminating alcohol consumption completely. First, we should note that both reasons refer to rather specific disadvantages of the prohibition—a good start. The acceptability of the first reason, however, depends on a hidden assumption that once we allow actions to be taken on the merits of one case, it will be impossible to stop actions on similar cases. We do not agree with this assumption, because we believe that there are plenty of steps in our legal system to prevent such actions if they appear unjustified. Thus, we judge this reason to be unacceptable. Such reasoning is an example of the slippery slope fallacy.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Slippery Slope: Making the assumption that a proposed step will set off an uncontrollable

chain of undesirable events, when procedures exist to prevent such a chain

of events.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The relevance of the second reason is questionable because even if this reason were true, the assumption linking the reason to the conclusion—the major goal of prohibiting alcohol advertising on radio and television is to eliminate alcohol consumption completely—is false. A more likely goal is to reduce consumption. Thus we reject this reason. We call this fallacy the searching for perfect solutions fallacy. It takes the form: A solution to X does not deserve our support unless it destroys the problem entirely. If we ever find a perfect solution, then we should adopt it. But because the fact that part of a problem would remain after a solution is tried does not mean the solution is unwise.

A particular solution may be vastly superior to no solution at all. It may move

us closer to solving the problem completely. If we waited for perfect solutions to emerge, we would often find ourselves paralyzed, unable to act. Here is another example of this fallacy: Why try to restrict people's access to abortion clinics in the United States? Even if you were successful, a woman seeking an abortion could still fly to Europe to acquire an abortion.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Searching for Perfect Solution: Falsely assuming that because part of a problem would remain after a solution is tried, the solution should not be adopted.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Discovering Other Common Reasoning Fallacies

We are now going to take you through some exercises in discovering more common fallacies. As you encounter each exercise, try to apply the fallacy, finding hints that we listed above. Once you have developed good fallacy-detection habits, you will be able to find most fallacies. Each exercise presents some reasoning that includes fallacies. We indicate why we believe the reasoning is fallacious and then name and define the fallacy.

Exercise A

It's about time that we make marijuana an option for people in chronic severe pain. We approve drugs when society reaches a consensus about their value, and there is clearly now a consensus for such approval. A recent survey of public opinion reported that 73 percent thought medical marijuana should be allowed.

In addition, the California Association for the Treatment of AIDS Victims supports smoking marijuana as a treatment option for AIDS patients. As a first step in analyzing for fallacies, let's outline the argument.

CONCLUSION: Smoking marijuana should be a medical option.

REASONS:

1. We approve drugs when a consensus of their medical value has been reached, and a recent survey shows a consensus approving marijuana as a medical treatment.

2. A California association supports medical marijuana use.

First, we should note that none of the reasons points out a specific advantage of medical marijuana; thus we should be wary from the start. Next, a close look at the wording in the first reason shows a shift in meaning of a key term, and this shift tricks us. The meaning of the word consensus shifts in such a way that it looks like she has made a relevant argument when she has not. Consensus for drug approval usually means the consensus of scientific researchers about its merits, which is a very different consensus than the agreement of the American public on an opinion poll. Thus the reason fails to make sense, and we should reject it.

We call this mistake in reasoning the equivocation fallacy. Whenever you see a key word in an argument used more than once, check to see that the meaning has not changed; if it has, be alert to the equivocation fallacy. Highly ambiguous terms or phrases are especially good candidates for the equivocation fallacy.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Equivocation: A key word is used with two or more meanings in an argument such that the argument fails to make sense once the shifts in meaning are recognized.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Well, even if there is tricky use of the word "consensus," don't the survey results by themselves still support the conclusion? They do only if we accept the assumption that when something is popular, then it must be good—a mistaken assumption. The public often has not sufficiently studied a problem to provide a reasoned judgment. Be wary of appeals to common opinion or to popular sentiment. We label this mistake in reasoning the appeal to popularity fallacy.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Appeal to Popularity (Ad populum): An attempt to justify a claim by appealing to

sentiments that large groups of people have in common; falsely assumes that anything

favored by a large group is desirable.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now, carefully examine the author's second reason. What assumption is being made? To prove that medical marijuana is desirable, she appeals to questionable authorities—a California Association. A position is not good just because the authorities are for it. What is important in determining the relevance of such reasoning is the evidence that the authorities are using in making their judgment. Unless we know that these authorities have special knowledge about this issue, we must treat this reason as a fallacy. Such a fallacy is called the

Appeal to Questionable Authority fallacy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Appeal to questionable authority: Supporting a conclusion by citing an authority who lacks special expertise on the issue at hand.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now let's examine some arguments related to another controversy: Should Congress approve a federally funded child-development program that would provide day-care centers for children?

Exercise B

I am against the government's child-development program. First, I am interested in protecting the children of this country. They need to be protected from social planners and self-righteous ideologues who would disrupt the normal course of life and tear them from their mothers and families to make them pawns in a universal scheme designed to produce infinite happiness in 20 years. Children should grow up with their mothers, not with a series of caretakers and nurses' aides. What is at issue is whether parents shall continue to have the right to form the characters of their children, or whether the State with all its power should be given the tools

and techniques for forming the young.

Let's again begin by outlining the argument.

CONCLUSION: The government's child development program is a mistake.

REASONS:

1. Our children need to be protected from social planners and self-righteous ideologues, who would disrupt the normal course of life and tear them from their families.

2. The parents, not the State, should have the right to form the characters their children. As critical readers and listeners, we should be looking for specific facts about the program. Do you find any specifics in the first reason? No. The reason is saturated with undefined and emotionally loaded generalities. We have italicized several of these terms in the passage. Such terms will typically generate negative emotions, which the writer or speaker hopes readers and listeners will associate with the position he is attacking. The writer is engaging in name-calling and emotional appeals. The use of emotionally charged negative terms serves to distract readers and listeners from the facts.

The writer has tricked us in another way. She states that the program will "tear them from their families and mothers," and the children will be "pawns in a universal scheme." Of course, nobody wants these things to happen to their children. However, the important question is whether in fact the bill will do these things. Not likely! The writer is playing two common tricks on us. First, she is appealing to our emotions with her choice of words, hoping that our emotional reactions will get us to agree with her conclusion. When communicators try to draw emotional reactions from people and then use that reaction to get them to agree to their conclusion, they commit the fallacy of an Appeal to Emotion. This fallacy occurs when your emotional reactions should not be relevant to the truth or falsity of a conclusion. Three of the most common places for finding this fallacy are in advertising, in political debate and in the courtroom.

Second, she has set up a position to attack which in fact does not exist, making it much easier to get us on her side. She has extended the opposition's position to an "easy-to-attack" position. The false assumption in this case is that the position attacked is the same as the position actually presented in the legislation. The lesson for the critical thinker is: When someone attacks aspects of a position, always check to see whether she is fairly representing the position. If she is not, you have located the straw-person fallacy.

A straw person is not real and is easy to knock down—as is the position attacked when someone commits the straw-person fallacy. The best way to check how fairly a position is being represented is to get the facts about all positions.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Appeals to Emotions: The use of emotionally charged language to distract readers and listeners from relevant reasons and evidence.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Straw Person: Distorting our opponent's point of view so that it is easy to attack; thus we attack a point of view that does not truly exist.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's now look closely at the second reason. The writer states that either parents have the right to form the characters of their children, or else the State should be given the decisive tools. For statements like this to be true, one must assume that there are only two choices. Are there? No! The writer has created a false dilemma. Isn't it possible for the child-development program to exist and also for the family to have a significant influence on the child? Always be cautious when controversies are treated as if only two choices are possible; there are usually more than two. When a communicator oversimplifies an issue by stating only two choices, the error is referred to as an either-or or false dilemma fallacy. To find either-or fallacies, be on the alert for phrases like the following:

either . . . or

the only alternative is

the two choices are

because A has not worked, only B will.

Seeing these phrases does not necessarily mean that you have located a fallacy. Sometimes there are only two options. These phrases are just caution signs causing you to pause and wonder: "But are there more than two options in this case?"

Can you see the false dilemma in the following interchange?

Citizen: I think that the decision by the United States to invade Iraq was a big

mistake.

Politician: Why do you hate America?

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Either-Or (Or False Dilemma): Assuming only two alternatives when there are more than two.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The following argument contains another fallacy involving a mistaken assumption. Try to locate the assumption.

Exercise C

Student: It doesn't make sense for you to give pop quizzes to your class, Professor Jones. It just makes a lot of extra work for you and makes the students nervous. Students should not need pop quizzes to motivate them to prepare for each class.

The advice to Professor Jones requires a faulty assumption to support the conclusion. That something should be true—students should not need pop quizzes to motivate them to prepare for class—in no way guarantees that what is true will conform to the prescription. Reality, or "what is," is often in conflict with "what should be."

Another common illustration of this reasoning error occurs when discussing proposals for government regulation. For instance, someone might argue that regulating advertising for children's television programs is undesirable because parents should turn the channel or shut off the television if advertising is deceptive. Perhaps parents in a perfect world would behave in this fashion.

Many parents, however, are too busy to monitor children's programming. When reasoning requires us to assume incorrectly that what we think should be matches what is, or what will be, it commits the wishful thinking fallacy. We would hope that what should be the case would guide our behavior. Yet many

observations convince us that just because advertisers, politicians, and authors should not mislead us is no protection against their regularly misleading us. The world around us is a poor imitation of what the world should be like.

Here's a final example of wishful thinking that might sound familiar to you.

I can't wait for summer vacation time, so I can get all those books read that I've put off reading during the school year.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Wishful Thinking: Making the faulty assumption that because we wish X were true or false, then X is indeed true or false.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Another confusion is responsible for an error in reasoning that we often encounter when seeking explanations for behavior. A brief conversation between college roommates illustrates the confusion.

Dan: I've noticed that Chuck has been acting really weird lately. He's acting really rude toward others and is making all kinds of messes in our residence hall and refusing to clean them up. What do you think is going on?

Kevin: That doesn't surprise me. He is just ajerk. To explain requires an analysis of why a behavior occurred. Explaining is demanding work that often tests the boundaries of what we know. In the above

example, "jerkhood" is an unsatisfactory explanation of Chuck's behavior.

When asked to explain why a certain behavior has occurred, it is frequently tempting to hide our ignorance of a complex sequence of causes by labeling or naming the behavior. Then we falsely assume that because we know the name, we know the cause.

We do so because the naming tricks us into believing we have identified something the person has or is that makes her act accordingly.

For example,

instead of specifying the complex set of internal and external factors that lead a person to manifest an angry emotion, such as problems with relationships, parental reinforcement practices, feelings of helplessness, lack of sleep, and life stressors, we say the person has a "bad temper" or that the person is hostile.

Such explanations oversimplify and prevent us from seeking more insightful understanding.

The following examples should heighten your alertness to this fallacy:

1. In response to Dad's heavy drinking, Mom is asked by her adult daughter, "Why is Dad behaving so strangely?" Mom replies, "He's having a midlife crisis."

2. A patient cries every time the counselor asks about his childhood. An intern who watched the counseling session asks the counselor, after the patient has left, "Why does he cry when you ask about his youth?" The counselor replies, "He's neurotic."

Neither respondent satisfactorily explained what happened. For instance, the specifics of dad's genes, job pressures, marital strife, and exercise habits could have provided the basis for explaining the heavy drinking. "A midlife crisis" is not only inadequate; it misleads. We think we know why dad is drinking heavily, but we don't.

Be alert for this error when people claim that they have discovered a cause for the behavior when all they have actually done is named it.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Explaining by Naming: Falsely assuming that because you have provided a name for some event or behavior that you have also adequately explained the event.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Looking for Diversions

Frequently, those trying to get an audience to accept some claim find that they can defend that claim by preventing the audience from taking too close a look at the relevant reasons. They prevent the close look by diversion tactics. As you look for fallacies, you will find it helpful to be especially alert to reasoning used by the communicator that diverts your attention from the most relevant reasons. For example, the Ad Hominem fallacy can fool us by diverting our attention too much to the nature of the person and too little to the legitimate

reasons. In this section, we present exercises that illustrate other fallacies that we are likely to detect if we ask the question, "Has the author tricked us by diverting our attention?"

Exercise D

Political speech: In the upcoming election, you have the opportunity to vote for a woman who represents the future of this great nation, who has fought for democracy and defended our flag, and who has been decisive, confident, and courageous in pursuing the American Dream. This is a caring woman who has supported our children and the environment and has helped move this country toward peace, prosperity, and freedom. A vote for Goodheart is a vote for truth, vision, and common sense.

Sounds like Ms. Good heart is a wonderful person, doesn't it? But the speech fails to provide any specifics about the senator's past record or present position on issues. Instead, it presents a series of virtue words that tend to be associated with deep-seated positive emotions. We call these virtue words "Glittering generalities,'" because they have such positive associations and are so general as to mean whatever the reader wants them to mean. The Glittering Generality device leads us to approve or accept a conclusion without examining relevant reasons, evidence, or specific advantages or disadvantages. The Glittering Generality is much like name-calling in reverse because name calling seeks to make us form a negative judgment without examining the evidence. The use of virtue words is a popular ploy of politicians because it serves to distract the reader or listener from specific actions or policies, which can more easily trigger disagreement.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Glittering Generality: The use of vague emotionally appealing virtue words that dispose us to approve something without closely examining the reasons.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Let's examine another very common diversionary device.

Exercise E

I don't understand why everyone is so upset about drug companies distorting research data in order to make their pain-killer drugs seem to be less dangerous to people's health than they actually are. Taking those drugs can't be that bad.

After all, there are still thousands of people using these drugs and getting pain relief from them.

What is the real issue? Is the public being misled about the safety of pain-killer drugs? But if the reader is not careful, his attention will be diverted to the issue of whether the public wants to use these drugs. When a writer or speaker shifts our attention from the issue, we can say that she has drawn a red herring across the trail of the original issue. Many of us are adept at committing the red herring fallacy, as the following example illustrates:

If the daughter is successful, the issue will become whether the mother is picking on her daughter, not why the daughter was out late.

You should normally have no difficulty spotting red herrings as long as you keep the real issue in mind as well as the kind of evidence needed to resolve it.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Red Herring: An irrelevant topic is presented to divert attention from the original issue and help to "win" an argument by shifting attention away from the argument and to another issue. The fallacy sequence in this instance is as follows: (a) Topic A is being discussed; (b) Topic B is introduced as though it is relevant to topic A, but it is not; and (c) Topic A is abandoned.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This sort of "reasoning" is fallacious because merely changing the topic of discussion hardly counts as an argument against a claim.

Sleight of Hand: Begging the Question

Our last illustrated fallacy is a particularly deceptive one. Sometimes a conclusion is supported by itself; only the words have been changed to fool the innocent!

For example, to argue that dropping out of school is undesirable because it is bad is to argue not at all. The conclusion is "proven" by the conclusion (in different words). Such an argument begs the question, rather than answering it.

Let's look at an example that is a little less obvious.

Programmed learning texts are clearly superior to traditional texts in learning effectiveness because it is highly advantageous for learning to have materials presented in a step-by-step fashion. Again, the reason supporting the conclusion restates the conclusion in different words. By definition, programmed learning is a step-by-step procedure. The writer is arguing that such a procedure is good because it is good. A legitimate reason would be one that points out a specific advantage to programmed learning such as greater retention of learned material.

Whenever a conclusion is assumed in the reasoning when it should have been proven, begging the question has occurred. When you outline the structure of an argument, check the reasons to be sure that they do not simply repeat the conclusion in different words and check to see that the conclusion is not used to prove the reasons. In case you are confused, let's illustrate with two examples, one argument that begs the question and one that does not.

(1) To allow the press to keep their sources confidential is very advantageous to the country because it increases the likelihood that individuals will report evidence against powerful people. (2) To allow the press to keep their sources confidential is very advantageous to the country because it is highly conducive to the interests of the larger community that private individuals should have the privilege of providing information

to the press without being identified. Paragraph (2) begs the question by basically repeating the conclusion. It fails to point out what the specific advantages are and simply repeats that confidentiality of sources is socially used.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Begging the Question: An argument in which the conclusion is assumed in the reasoning.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

USING THIS CRITICAL QUESTION

When you spot a fallacy, you have found a legitimate basis for rejecting the argument. But in the spirit of constructive critical thinking, you want to continue the discussion of the issue. Unfortunately, the author of a book or article is unavailable for more conversation. But in those instances where the fallacy occurred in an oral argument, your best bet for an enduring conversation is to ask the person who committed the fallacy if there is not a better reason for the conclusion. For example, if a red herring fallacy occurs, ask the speaker if it would be possible to return to the original issue.

Summary of Reasoning Errors

We have taken you through exercises that illustrate a number of ways in which reasoning may be faulty. We have not listed all the ways, but we have given you a good start. We have saved some additional fallacies for later chapters because you are most likely to spot them when you focus on the particular question central to that chapter. As you encounter each additional fallacy, be sure to add it to your fallacy list.

To find reasoning fallacies, keep in mind what kinds of reasons are good reasons—that is, the evidence and the moral principles relevant to the issue.

Reasoning should be rejected whenever you have found mistaken assumptions, distractions, or support for the conclusion that already assumes the truth of the conclusion. Reasoning should be approached cautiously when it appeals to group-approved attitudes and to authority. You should always ask, "Are there good reasons to consider such appeals as persuasive evidence?"

A precautionary note is in order here: Do not automatically reject reasoning that relies on appeals to authority or group-approved attitudes. Carefully evaluate such reasoning.

For example, if most physicians in the country choose to take up jogging, that information is important to consider in deciding whether jogging is

beneficial. Some authorities do possess valuable information. Because of their

importance as a source of evidence, we discuss appeals to authority in detail in the next chapter.

Expanding Your Knowledge of Fallacies

We recommend that you consult texts and some web sites to expand your awareness and understanding of reasoning fallacies. Darner's Attacking Faulty Reasoning is a good source to help you become more familiar with reasoning fallacies. There are dozens of fallacy lists on the web, which vary greatly in quality. A few of the more helpful sites, which provide descriptions and examples of numerous fallacies, are listed below:

The Nizkor Project: Fallacies, http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/

The Fallacy Zoo, by Brian Yoder: (list of basic fallacies with examples) http:// www.goodart.org/fallazoo.htm

The Fallacy Files by Gary Curtis http://www.fallacyfiles.org/

Stephen's Guide to the Logical Fallacies http://www.datanation.com/fallacies/

Fallacies and Your Own Writing and Speaking

When you communicate, you necessarily engage in reasoning. If your purpose is to present a well-reasoned argument, in which you do not want to "trick" the reader into agreeing with you, then you will want to avoid committing reasoning fallacies. Awareness of possible errors committed by writers provides you with warnings to heed when you construct your own arguments.

You can avoid fallacies by checking your own assumptions very carefully, by remembering that most controversial issues require you to get specific about advantages and disadvantages, and by keeping a checklist handy of possible reasoning fallacies.

Practice Exercises

Critical Question: Are there any fallacies in the reasoning?Try to identify fallacies in the reasoning in each of the three practice passages.

Passage 1

The surgeon general has overstepped his bounds by recommending that explicit sex education begin as early as third grade. It is obvious that he is yet another victim of the AIDS hysteria sweeping the nation. Unfortunately, his media-influenced announcement has given new life to those who favor explicit sex education—even to the detriment of the nation's children.

Sexuality has always been a topic of conversation reserved for the family. Only recently has sex education been forced on young children. The surgeon general's recommendation removes the role of the family entirely. It should be up to parents to explain sex to their children in a manner with which they are comfortable. Sex education exclusive of the family is stripped of values or any sense of morality, and should thus be discouraged. For years families have taken the responsibility of sex education, and that's the way it should

remain.

Sex education in schools encourages experimentation. Kids are curious. Letting them in on the secret of sex at such a young age will promote blatant promiscuity. Frank discussions of sex are embarrassing for children, and they destroy the natural modesty of girls.

Passage 2

Sandra: I don't see why you are so against permitting beer to be sold at the new University Student Union. After all, a survey of our students shows that 80 percent are in favor of the proposal.

Joe: Of course, you will be in favor of serving any alcoholic beverage at any time anywhere. You are one of the biggest alcoholics on our campus.

Passage 3

Bill: Countries that harbor terrorists who want to destroy the United States must be considered enemies of the United States. Any country that does not relinquish terrorists to the American justice system is clearly on the side of the terrorists. This sort of action means that the leaders of these countries do not wish to see justice done to the terrorists and care more about hiding murderers, rapists, thieves, and anti-democrats.

Taylor: That's exactly the kind of argument that I would expect from someone who has relatives who have worked for the CIA. But it seems to me that once you start labeling countries that disagree with America on policy as enemies, then eventually almost all countries will be considered our enemies, and we will be left

with no allies.

Bill: If that's the case, too bad. America stands for freedom, for democracy, and for truth. So it can stand against the world. Besides, the United States should be able to convince countries hostile to the United States of the error of their ways because our beliefs have a strong religious foundation.

Taylor: Do you really think most religious people are in favor of war? A Gallup poll last week found that 75 percent of highly religious people didn't think we should go to war with countries harboring terrorists.

Bill: I think that's an overestimate. How many people did they survey? Taylor: I'm not sure. But getting back to your original issue, the biggest problem with a tough stand against countries that harbor terrorists is that such a policy is not going to wipe out terrorism in the world.

Bill: Why do you keep defending the terrorists? I thought you were a patriot. Besides, this is a democracy, and most Americans agree with me.

Sample Responses

Passage 1

CONCLUSION: Sex education should not be taught in schools.

REASONS:

1. The Surgeon General's report reflects hysteria.

2. The report removes the role of the family entirely.

3. It is the job of parents.

4. Education encourages promiscuity.

The author begins the argument by attacking the surgeon general rather than the issue. She claims that the recommendation is a by-product of the AIDS hysteria rather than extensive research. Her suggestion that the surgeon general issues reports in reaction to hot topics in the media undermines his credibility and character and is therefore ad hominem. The second paragraph is a straw-person fallacy because it implies that the goal of sex education is to supply all the child's sex education.

Her third reason confuses "what is" with "what should be." Just because sex education should be up to the parents does not mean that they will provide education.

The fourth reason presents a false dilemma—either keep sex education out of the schools or face morally loose, value-free children. But isn't it possible to have morally loose children even when sex education is taking place in the home? Isn't it also a possibility that both parents and the schools can play a role in sex education? Might not education result in children who are prepared to handle the issue of sex in their lives rather than morally deficient delinquents?

Passage 2

SANDRA'S CONCLUSION: Beer should be served at the University Union.

SANDRA'S REASON: Most students are in favor of the idea.

JOE'S CONCLUSION: Beer should not be served in the University Union (implied).

JOE'S REASON: We should not listen to Sandra's argument because she is an alcoholic.

Both Sandra and Joe commit fallacies in their arguments. Sandra bases her claim about the desirability of beer in the Union on the majority view of students that beer should be served. She makes the erroneous assumption that if the majority favors an action, the action is proper. Students might be for the proposal, but

they also may have given little thought to the advantages and disadvantages of making beer more easily available.

Joe commits two fallacies in his tiny argument. First, he attacks Sandra, rather than addressing Sandra's reasoning. Sandra's alleged alcoholism is not the issue.

She provides a reason for her support for beer in the Union; Joe ignores that reason and attacks her instead. Second, Joe responds to a straw man argument when he responds to Sandra by extending what she did say to an extreme position that she did not take in her statement. Nowhere in her argument did Sandra favor

drinking with no restrictions.

Are there Any Fallacies in the Reasoning?

Once you have identified the reasons, you want to determine whether the author used any reasoning tricks, or fallacies. If you identify a fallacy in reasoning, that reason does not provide good support for the conclusion. Consequently, you would not want to accept an author's conclusion on the basis of that reason. If the author

provides no good reasons, you would not want to accept her conclusion. Thus, looking for fallacies in reasoning is another important step in determining whether you will accept or reject the author's conclusion.