How GOOD IS THE EVIDENCE: PERSONAL OBSERVATION, RESEARCH STUDIES, CASE, EXAMPLES, and ANALOGIES?

In this chapter, we continue our evaluation of evidence. We focus on four common kinds of evidence: personal observation, research studies, case examples, and analogies. We need to question each of these when we encounter them as evidence.

Personal ObservationCritical Question: How good is the evidence: personal observation, research studies, case examples, and analogies

One valuable kind of evidence is personal observation, the basis for much scientific research. For example, we feel confident of something we actually see. Thus, we tend to rely on eyewitness testimony as evidence. A difficulty with personal observation, however, is the tendency to see or hear what we wish to see or hear, selecting and remembering those aspects of an experience that are most consistent with our previous experience and background.

Observers, unlike certain mirrors, do not give us "pure" observations. What we "see" and report is filtered through a set of values, biases, attitudes, and expectations. Because of such influences, observers often disagree about what they perceive. Thus, we should be wary of reliance on observations made by any single observer in situations in which we might expect observations among observers to vary.

Three illustrations should help you see the danger of relying on personal observation as evidence:

• A player says he crossed the end zone and the referee says the player stepped out of bounds first.

• There is a car accident at a busy intersection. The drivers blame each other. Witnesses alternately blame the drivers and a third car that sped off.

• You send what you believe to be a friendly e-mail to a friend. Your friend responds to you wanting to know why you sent such a mean note to her. While personal observations can often be valuable sources of evidence, we need to recognize that they are not unbiased "mirrors of reality"; and when they are used to support controversial conclusions, we should seek verification by other observers as well as other kinds of evidence to support the conclusion. For example, if an employee complains that certain remarks made by her boss are discriminatory, the claim is more credible if others who heard the remarks also think the comments were discriminatory. Also, remember that observational reports get increasingly problematic as the time

between the observation and the report of the observation increases.

When reports of observations in newspapers, magazines, books, television, and the Internet are used as evidence, you need to determine whether there are good reasons to rely on such reports. The most reliable reports will be based on recent observations made by several people observing under optimal conditions who have no apparent, strong expectations or biases related to the event being observed.

Research Studies as Evidence

"Studies show..."

"Research investigators have found in a recent survey that..."

"A report in the New England Journal of Medicine indicates . . ."

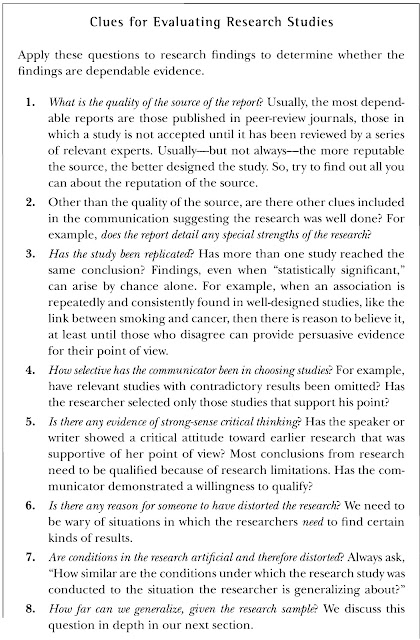

One form of authority that relies a great deal on observation and often carries special weight is the research study: usually a systematic collection of observations by people trained to do scientific research. How dependable are research findings? Like appeals to any authority, we cannot tell about the dependability

of research findings until we ask lots of questions.

Society has turned to the scientific method as an important guide for determining the facts because the relationships among events in our world are very complex, and because humans are fallible in their observations and theories about these events. The scientific method attempts to avoid many of the built-in biases in our observations of the world and in our intuition and common sense.

What is special about the scientific method? Above all, it seeks information in the form of publicly verifiable data—that is, data obtained under conditions such that other qualified people can make similar observations and see whether they get the same results. Thus, for example, if one researcher reports that she was able to achieve cold fusion in she lab, the experiment would seem more credible if other researchers could obtain the same results.

A second major characteristic of scientific method is control—that is, the using of special procedures to reduce error in observations and in the interpretation of research findings. For example, if bias in observations may be a major problem, researchers might try to control this kind of error by using multiple observers to see how well they agree with one another. Physical scientists frequently maximize control by studying problems in the laboratory so that they can minimize extraneous factors. Unfortunately, control is usually more difficult in the social world than in the physical world; thus it is very difficult to successfully apply the scientific method to many questions about complex human behavior.

Precision in language is a third major component of the scientific method. Concepts are often confusing, obscure, and ambiguous. Scientific method tries to be precise and consistent in its use of language. While there is much more to science than we can discuss here, we want you to keep in mind that scientific research, when conducted well, is one of our best sources of evidence because it emphasizes verifiability, control, and precision.

Problems with Research Findings

Unfortunately, the fact that research has been applied to a problem does not necessarily mean that the research evidence is dependable evidence or that the interpretations of the meaning of the evidence are accurate. Like appeals to any source, appeals to research evidence must be approached with caution.

Also, some questions, particularly those that focus on human behavior, can be answered only tentatively even with the best of evidence. Thus, there are a number of important questions we want to ask about research studies before we decide how much to depend on their conclusions.

When communicators appeal to research as a source of evidence, you should remember the following:

1. Research varies greatly in quality; we should rely more on some research studies than others. There is well-done research and there is poorly done research, and we should rely more on the former. Because the research process is so complex and subject to so many external influences, even those well-trained in research practices sometimes conduct research studies that have important deficiencies; publication in a scientific journal does not guarantee that a research study is not flawed in important ways.

2. Research findings often contradict one another. Thus, single research studies presented out of the context of the family of research studies that investigate the question often provide misleading conclusions. Research

findings that most deserve our attention are those that have been repeated by more than one researcher or group of researchers. We need to always ask the question: "Have other researchers verified the findings?"

3. Research findings do not prove conclusions. At best, they support conclusions. Research findings do not speak for themselves! Researchers must always interpret the meaning of their findings, and all findings can be

interpreted in more than one way. Thus, researchers' conclusions should not be treated as demonstrated "truths." When you encounter statements such as "research findings show..." you should retranslated them into "researchers interpret their research findings as showing . . ."

4. Like all of us, researchers have expectations, attitudes, values, and needs that bias the questions they ask, the way they conduct their research, and the way they interpret their research findings. For example, scientists

often have an emotional investment in a particular hypothesis. When the American Sugar Institute is paying for your summer research grant, it is very difficult to then "find" that sugar consumption among teenagers is excessive. Like all fallible human beings, scientists may find it difficult to objectively treat data that conflict with their hypothesis. A major strength of scientific research is that it tries to make public its procedures and results so that others can judge the merit of the research and then try to replicate it. However, regardless of how objective a scientific report may seem, important subjective elements are always involved.

Speakers and writers often distort or simplify research conclusions. Major discrepancies may occur between the conclusion merited by the original research and the use of the evidence to support a communicator's beliefs. For example, researchers may carefully qualify their own conclusions in their original research report only to have the conclusions used by others without the qualifications. Research "facts" change over time, especially claims about human behavior.

For example, all of the following research "facts" have been reported by major scientific sources, yet have been "refuted" by recent research evidence:

Prozac is completely safe when taken by children.

It is important to drink eight glasses of water a day.

Depression is caused entirely by chemical imbalances in the brain.

Improper attachment to parents causes anti-social behavior in children.

Research varies in how artificial it is. Often, to achieve the goal of control, research loses some of its "real-world" quality. The more artificial the research, the more difficult it is to generalize from the research study to

the world outside. The problem of research artificiality is especially evident in research studying complex social behavior. For example, social scientists will have people sit in a room with a computer to play "games"

that involve testing people's reasoning processes. The researchers are trying to figure out why people make certain decisions when confronted with different scenarios. However, we should ask, "Is sitting at the computer while thinking through hypothetical situations too artificial to tell us much about the way people make decisions when confronted with real dilemmas?"

The need for financial gain, status, security, and other factors can affect research outcomes. Researchers are human beings, not computers. Thus, it is extremely difficult for them to be totally objective. For example, researchers who want to find a certain outcome through their research may interpret their results in such a way to find the desired outcome. Pressures to obtain grants, tenure, or other personal rewards might ultimately

affect the way in which researchers interpret their data. As you can see, despite the many positive qualities of research evidence, need to avoid embracing research conclusions prematurely.

Generalizing from the Research Sample

Speakers and writers usually use research reports to support generalizations, that is, claims about events in general. For example, "the medication was effective in treating cancer for the patients in the study" is not a generalization; "the medication cures cancer" is. The ability to generalize from research findings depends on the number, breadth, and randomness of events or people the researchers study.

The process of selecting events or persons to study is called sampling. Because researchers can never study all events or people about which they want to generalize, they must choose some way to sample; and some ways are preferable to others. You need to keep several important considerations in mind when evaluating the research sample:

1. The sample must be large enough to justify the generalization or conclusion. In most cases, the more events or people researchers observe, the more dependable their conclusion. If we want to form a general belief about how often college students receive help from others on term papers, we are better off studying 100 college students than studying 10.

2. The sample must possess as much breadth, or diversity, as the types of events about which conclusions are to be drawn. For example, if researchers want to generalize about college students' drinking habits in general, their evidence should be based on the sampling of a variety of different kinds of college students in a variety of different kinds of college settings. Students at a small private school in the Midwest may have different drinking habits than students at a large public school on the West Coast; thus, a study of students attending only one school would lack breadth of sampling.

3. The more random the sample, the better. When researchers randomly

sample, they try to make sure that all events about which they want to

generalize have an equal chance of getting sampled; they try to avoid a biased sample. Major polls, like the Gallop poll, for example, always try to sample randomly. This keeps them from getting groups of events or people that have biased characteristics. Do you see how each of the following samples has biased haracteristics?

a. People who volunteer to be interviewed about frequency of sexual activity.

b. People who are at home at 2:30 P.M. to answer their phone.

c. Readers of a popular women's magazine who clip and complete mail-in surveys. Thus, we want to ask of all research studies, "How many events or people did they sample, how much breadth did the sample have, and how random was the sample?"

A common problem that stems from not paying enough attention to the limits of sampling is for communicators to overgeneralize research findings. They state a generalization that is much broader than that warranted by the research. In Chapter 7, we referred to such overgeneralizing as the Hasty Generalization fallacy. Let's take a close look at a research over generalization: Alcohol consumption is at an all-time high at colleges nationwide. A recent survey conducted by Drinksville University found that of the 250 people surveyed,

89 percent drink on a semi-regular basis. Sampling procedures prohibit such a broad generalization. The research report implies the conclusion can be applied to all campuses, when the research studied only one campus. We don't even know whether the conclusion can be applied to that campus, because we don't know how randomly researchers

sampled from it. The research report is flawed because it gready overgeneralizes.

Remember: We can generalize only to people and events that are like those that we have studied in the research!

Biased Surveys and Questionnaires

It's early evening. You have just finished dinner. The phone rings. "We're conducting a survey of public opinion. Will you answer a few questions?" If you answer "yes," you will be among thousands who annually take part in surveys— one of the research methods you will encounter most frequently. Think how often you hear the phrase "according to recent polls."

Surveys and questionnaires are usually used to measure people's attitudes and beliefs. Just how dependable are they? It depends! Survey responses are subject to many influences; thus, one has to be very cautious in interpreting their meaning. Let's examine some of these influences.

First, for survey responses to be meaningful, they must be answered honestly. That is, verbal reports need to mirror actual beliefs and attitudes. Yet, for a variety of reasons, people frequently shade the truth. For example, they may give answers they think they ought to give, rather than answers that reflect their true beliefs. They may experience hostility toward the questionnaire or toward the kind of question asked. They may give too little thought to the question. If you have ever been a survey participant, you can probably

think of other influences.

Remember: You cannot assume that verbal reports accurately reflect true attitudes.

Second, many survey questions are ambiguous in their wording; the questions are subject to multiple interpretations. Different individuals may in essence be responding to different questions! For example, imagine the multiple possible interpretations of the following survey question: "Do you think there is quality programming on television?" The more ambiguous the wording of a survey, the less credibility you can place in the results.

You should always ask the question: "How were the survey questions worded?" Usually, the more specifically worded a question, the more likely that different individuals will interpret it similarly.

Third, surveys contain many built-in biases that make them even more suspect. Two of the most important are biased wording and biased context. Biased wording of a question is a common problem; a small change in how a question is asked can have a major effect on how a question is answered. Let's examine a conclusion based on a recent poll and then look at the survey question.

A college professor found that 86 percent of respondents believe that President Bush has failed the American people with respect to his handling of the war in Iraq. Now let's look closely at the survey question: "What do you think about the President's misguided efforts in the war in Iraq?" Look carefully at this question. Do you see the built-in bias? The "leading" words are "the President's misguided efforts." Wouldn't the responses have been quite different if the question had read: "What do you think about the President's attempt to bring democracy, markets, and freedom to the Iraqi people?" Thus, the responses obtained here are not an accurate indicator of attitudes concerning President Bush's handling of the war in Iraq.

Survey and questionnaire data must always be examined for possible bias. Look carefully at the wording of the questions^. Here is another example. We have emphasized the word that demonstrates the bias.

QUESTION: Should poor people who refuse to get a job be allowed to receive welfare benefits}

CONCLUSION: Ninety-three percent of people responding believe poor people should not receive welfare benefits.

The effect of context on an answer to a question can also be powerful. Even answers to identical questions can vary from poll to poll depending on how the questionnaire is presented and how the question is embedded in the survey. The following question was included in two recent surveys: "Do you think we should lower the drinking age from 21?" In one survey, the question was preceded by another question: "Do you think the right to vote should be given to children at the age of 18 as it currently is?" In the other survey, no preceding question occurred. Not surprisingly, the two surveys showed different results. Can you see how the context might have affected respondents? Another important contextual factor is length. In long surveys, people may respond differently to later items than to earlier items simply because they get tired. Be alert to contextual factors when evaluating survey results. Because the way people respond to surveys is affected by many unknown factors, such as the need to please or the interpretation of the question, should we ever treat survey evidence as good evidence? There are heated debates about this issue, but our answer is "yes," as long as we are careful and do not generalize further than warranted. Some surveys are more reputable than others. The better the quality of the survey, the more you should be influenced by the results.

Our recommendation is to examine survey procedures carefully before accepting survey results. Once you have ascertained the quality of the procedures, you can choose to generate your own qualified generalization—one that takes into account any biases you might have found. Even biased surveys can be informative; but you need to know the biases in order to not be unduly persuaded by the findings.

Critical Evaluation of a Research-Based Argument

Let's now use our questions about research to evaluate the following argument in which research evidence has been used to support a conclusion. Parents who push their children to study frequently end up causing their children to dislike reading, a recent study argues. The researchers studied 56 children in the sixth grade and found that those who reported the greatest dislike for reading were the ones whose parents frequently forced them to read. Alternatively, students who reported enjoying reading had less domineering parents. "The

more demanding the parents were with studying, the less likely the child was to enjoy reading on his or her own," claim Stanley and Livingstone in the August issue of Educator's War Chest. The study was conducted at Little Creek elementary school in Phoenix, Arizona. The study found that if not forced to study, children

were more likely to pick up a book in their free time. "It seems that there is a natural inclination to rebel against one's parents in children, and one way to manifest this inclination is to refuse to read if the child's parents force the child to study," reported Stanley and Livingstone.

The research is presented here in an uncritical fashion. We see no sign of strong-sense critical thinking. The report makes no references to special strengths or weaknesses of the study, although it does provides some detail about the research procedures so that we can make judgments about its worth as the basis of a generalization. There is no indication of whether the study has been replicated. Also, we do not know how selective the communicator has been in choosing studies, nor how this research fits into the broader context of research on children and their enjoyment of reading.

We do not know what benefits publishing this study may have had for the researchers.

Have the researchers and passage author overgeneralized? The sample is small—56—and it lacks breadth and randomness because it is restricted to one elementary school in the Southwest. We need to ask many questions about the sampling. How were these children selected? How was the study advertised to the parents? Could there have been a bias in the kind of parents willing to sign up for such a study? Would we have gotten similar results if we had randomly chosen families from a large number of schools throughout the country? This passage clearly illustrates a case of over generalization !

Are the questionnaires biased? Consider being a parent and completing a questionnaire about how controlling you are. Don't you think we could raise doubts about the accuracy of responses to such a questionnaire? Too little information is given about the wording of the questionnaires or about the arrangement of questionnaire items to judge the ambiguity of the item wording and the possibility of biased wording and biased context.

We have raised enough questions about the above passage to be wary of its factual claims. We would want to rely on much more research before we could conclude that these claims are dependable.

Let's now look at a very different source of evidence.

Case Examples as Evidence

President of a large university: "Of course our students can move on to high paying jobs and further study at large universities. Why, just this past year we sent one of our students, Mary Nicexample, off to law school at Harvard. In her first year Mary remained in the top five percent of her class. Therefore, our students can certainly achieve remarkable success at elite universities."

A frequently used kind of evidence that contrasts markedly to the kind of research study that we have just described, which emphasized studying large representative samples, is the use of a detailed description of

one or several individuals or events to support a conclusion. Such descriptions are usually based on observations or interviews and vary from being in depth and thorough to being superficial. We call such descriptions case examples.

Communicators often begin persuasive presentations with dramatic descriptions of cases. For example, one way to argue to increase the drinking age is to tell heart-wrenching stories of young people's dying in car accidents when the driver was young and drunk. Case examples are often compelling to us because of their colorfulness and their interesting details, which make them easy to visualize. Political candidates have increasingly resorted to case examples in their speeches, knowing that the rich details of cases generate an emotional reaction. Such cases, however, should be viewed more as striking examples or anecdotes than as proof, and we must be very suspicious of their use as evidence.

Dramatic cases appeal to our emotions and distract us from seeking other more relevant research evidence. For example, imagine a story about a man who tortured and murdered his numerous victims. The human drama of these crimes may lead us to ignore the fact that such a case is rare and that over the past 30 years 119 inmates with capital sentences were found to be innocent and released from prison.

Be wary of striking case examples as proof!

Although case examples will be consistent with a conclusion, do not let that consistency fool you. Always ask yourself: "Is the example typical?" "Are there powerful counterexamples?" "Are there biases in how the example is reported?" Are there times that case examples can be useful, even if they are not good evidence? Certainly! Like personal experiences, they demonstrate important possibilities and put a personal face on abstract statistics. They make it easier for people to relate to an issue and thus take more interest in it.

Analogies as Evidence

Look closely at the structure of the following brief arguments, paying special attention to the reason supporting the conclusion. Adults cannot learn all of the intricacies of new computer technology. Trying to teach adults new computer systems is like trying to teach an old dog new tricks.

As an educator it is important to weed out problem students early and take care of the problems they present because one bad egg ruins the omelet. These two arguments use analogies as evidence, a very different kind of evidence from what we have previously been evaluating. How do we decide whether it is good evidence? Before reading on, try to determine the persuasiveness of the two arguments.

Communicators often use resemblance as a form of evidence. They reason in the following way: "If these two things are alike in one respect, then they will probably be alike in other respects as well."

For example, when bipolar disorder (manic depression) was first identified, psychologists frequently treated it similarly to depression because both shared the common characteristics of severe depression. We reason in a similar fashion when we choose to buy a CD because a friend recommends it. We reason that because we resemble each other in a number of likes and dislikes, we will enjoy the same music.

An argument that uses a well-known similarity between two things as the basis for a conclusion about a relatively unknown characteristic of one of those things is an argument by analogy. Reasoning by analogy is a common way of presenting evidence to support a conclusion.

Analogies both stimulate insights and deceive us. For example, analogies have been highly productive in scientific and legal reasoning. When we infer conclusions about humans on the basis of research with mice, we reason by analogy. Much of our thinking about the structure of the atom is analogical reasoning. When we make a decision in a legal case, we may base that decision on the similarity of that case to preceding cases. For example, when judges approach the question of whether restricting pornographic material violates

the constitutional protection of free speech and freedom of expression, they must decide whether the potentially obscene pornographic material is analogous to freedom of speech; thus, they reason by analogy. Such reasoning can be quite insightful and persuasive.

Identifying and Comprehending Analogies

Accurate analogies are powerful, but are often difficult for people to evaluate. Analogies compare two known things to allow the reader to better understand the relationship to something that is unfamiliar. To be able to identify such comparisons, it is important to understand how analogies are structured. The first part of an analogy involves a familiar object or concept. That object or concept is being compared to another familiar object or concept. The second part is the relationship between the familiar objects or concepts. This relationship is used to create a principle that can be used to assist the understanding of a different object or concept. Finally, the relationship of the new or unfamiliar object or concept is described in the same format as the known object or concept. For example, "Relearning geometry is like riding a bike. Once you start, it all comes back to you." In the preceding analogy, riding a bicycle, the known, is used to explain relearning geometry, the unknown. We are familiar with the idea of getting on a bike after a period of time and "it all coming back to us" as we start to ride again. The analogy, therefore, explains relearning geometry in

the same way, arguing if one simply starts to do geometry problems, remembering how to do such problems will simply come back to the person.

Once the nature and structure of analogies is understood, you should be able to identify analogies in arguments. It is especially important to identify analogies when they are used to set the tone of the conversation. Such analogies are used to "frame" an argument. To identify framing analogies, look for comparisons that are used to not only explain a point, but also to influence the direction a discussion will take.

For example, in the 2004 presidential election, the war in Iraq was an important issue. Opponents of the war used the analogy comparing the war in Iraq to the Vietnam War. The use of Vietnam as an analogy to the war in Iraq

was not only an attempt to explain what is happening in Iraq now, but also to cause people to look negatively upon the war in Iraq. Conversely, proponents of the war in Iraq used the analogy comparing the war to world War II. World

War II carries with it more positive connotations than does the Vietnam War, so this analogy was used to reframe the discussion in terms more favorable to the war in Iraq. Always look for comparisons that attempt to direct the reaction to an object through framing. A careful evaluation of framing analogies will prevent you from being misled by a potentially deceptive analogy.

Framing analogies is not the only thing to be wary of when looking for analogies in arguments. One must also be careful when evaluating arguments that use overly emotional comparisons. For example, one person in arguing against the estate tax recently compared the tax to the Holocaust. Who could possibly be in favor of a tax that is the equivalent of the Holocaust? However, we must evaluate the analogy to see whether it is really accurate or simply an emotion-laden comparison intended to coerce people into agreeing with a certain perspective by making the alternative seem ridiculous. After all, regardless of what one thinks about the estate tax, it is not responsible for the deaths of millions of people. Overly emotional analogies cloud the real issues

in arguments and prevent substantive discourse. Try to identify comparisons made that contain significant emotional connotations to avoid being deceived by these analogies.

Evaluating Analogies

Because analogical reasoning is so common and has the potential to be both persuasive and faulty, you will find it very useful to recognize such reasoning and know how to systematically evaluate it. To evaluate the quality of an analogy, you need to focus on two factors.

1. The number of ways the two things being compared are similar and different.

2. The relevance of the similarities and the differences.

A word of caution: You can almost always find some similarities between any two things. So, analogical reasoning will not be persuasive simply because of many similarities. Strong analogies will be ones in which the two things we compare possess relevant similarities and lack relevant differences. All analogies try to illustrate underlying principles. Relevant similarities and differences are ones that directly relate to the underlying principle illustrated by the analogy.

Let's check out the soundness of the following argument by analogy.

I do not allow my dog to run around the neighborhood getting into trouble, so why shouldn't I enforce an 8 o'clock curfew on my 16-year old? I am responsible for keeping my daughter safe, as well as responsible for what she might do when she is out. My dog stays in the yard, and I want my daughter to stay in the house.

This way, I know exactly what both are doing.

A major similarity between a pet and a child is that both are thought of as not being full citizens with all the rights and responsibilities of adults. Plus, as the speaker asserts, he is responsible for keeping his dog and daughter safe. We note some relevant differences, however. A dog is a pet who lacks higher order thinking skills and cannot assess right and wrong. A daughter, however, is a human being with the cognitive capacity to tell when things are right and wrong and when she should not do something that might get her (or her parents) in trouble. Also, as a human, she has certain rights and deserves a certain amount of respect for her autonomy.

Thus, because a daughter can do things a dog cannot, the differences are relevant in assessing the analogy.

The failure of the analogy to allow for the above listed distinctions causes it to fail to provide strong support for the conclusion.

Another strategy that may help you evaluate reasoning by analogy is to generate alternative analogies for understanding the same phenomenon that the author or speaker is trying to understand. Such analogies may either support or contradict the conclusions inferred from the original analogy. If they contradict the conclusion, they then reveal problems in the initial reasoning by analogy. For example, when authors argue that pornography should be banned because it is harmful to women, as well as to all who view it, they are using a particular analogy to draw certain conclusions about pornography: Pornography is like a form of discrimination, as well as a means by which people are taught women are nothing but sex objects. Others, however, have offered alternative analogies, arguing that pornography is "a statement of women's sexual

liberation." Note how thinking about this different analogy may create doubts about the persuasiveness of the original analogy.

A productive way to generate your own analogies is the following:

1. Identify some important features of what you are studying.

2. Try to identify other situations with which you are familiar that have some similar features. Give free rein to your imagination. Brainstorm. Try to imagine diverse situations.

3. Try to determine whether the familiar situation can provide you with some insights about the unfamiliar situation.

For example, in thinking about pornography, you could try to think of other situations in which people repeatedly think something is demeaning because of the way people are treated in a given situation, or because of what watching something might cause others to do. Do segregation, racist/sexist jokes, or employment discrimination come to mind? How about arguments' claiming playing violent video games, watching action movies, or listening to heavy metal music causes children to act violently? Do they trigger other ways to think about pornography? You should now be capable of systematically evaluating the two brief analogical arguments at the beginning of this section. Ask the questions you need to ask to determine the structure of the argument.

Then, ask the questions to evaluate the argument. Look for relevant similarities and differences. Usually, the greater the ratio of relevant similarities to relevant differences, the stronger the analogy. An analogy is especially compelling if you can find no relevant difference and you can find good evidence that the relevant similarities do indeed exist.

We found a relevant difference that weakens each of our two initial sample analogies. Check your evaluation against our list.

(First example) Learning computer skills involves cognitive capabilities well within those of your average adult; teaching "an old dog new tricks" involves training an animal with lower cognitive abilities, who is set in his ways, how to obey a command he may never have heard before. Learning computer skills is not the same as classically conditioning an animal.

(Second example) The interactions of students in a classroom environment are very complex. The effect any one student might have on the group cannot easily be determined, just as the effects the group might have on the individual are difficult to predict. Conversely, a rotten egg will definitely spoil any food made from it. Also, it is problematic to think of people as unchanging objects, such as rotten eggs, that have no potential for growth and change.

Analogies that trick or deceive us fit our definition of a reasoning fallacy; such deception is called the Faulty Analogy fallacy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

F: Faulty Analogy: Occurs when an analogy is proposed in which there are important relevant dissimilarities.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In one sense, all analogies are faulty, because they make the mistaken assumption that because two things are alike in one or more respects, they are necessarily alike in some other important respect. It is probably best for you to think of analogies as varying from very weak to very strong. But even the best analogies are only suggestive. Thus if an author draws a conclusion about one case from a comparison to another case, then she should provide further evidence to support the principle revealed by the most significant similarity.

Summary

This chapter has continued our focus on the evaluation of evidence. We have discussed the following kinds of evidence: observation, research studies, case examples, and analogies. Each source has its strengths and weaknesses. Usually, you can rely most on those claims that writers or speakers support directly by extensive scientific research. However, many issues have not been settled by scientific research, and consequently, communicators must rely on research that is not conclusive and on other sources of evidence. You should be especially wary of claims supported by biased observation, dramatic case examples, poorly designed research, or faulty analogies. When you encounter any evidence, you should try to determine its quality by asking, "How good is the evidence?"

Practice Exercises

Critical Question: How good is the evidence?

Evaluate each of these practice passages by examining the quality of the evidence provided.

Passage 1

Are children of alcoholics more likely to be alcoholics themselves? In answering the question, researchers sampled 451 people in Alcoholics Anonymous to see how many would say that one, or both, of their parents were alcoholics. People in AA used in the study currendy attend AA somewhere in Ohio, Michigan, or Indiana and were asked by people in charge of the local AA programs to volunteer to fill out a survey. The research found that 77 percent of the respondents had at least one parent they classified as an alcoholic. The study also surveyed 451 people randomly from the same states who claim not to be heavy drinkers. Of the non heavy drinkers, 23 percent would label at least one of their parents as alcoholic.

Passage 2

I think California's "three strikes law" is a great idea. Why should criminals be given unlimited chances to continue to re-offend? We give a batter only three attempts to swing and hit a ball, so why does a criminal deserve any better? Three swings and misses and you are out; three offenses and convictions and

you are in, jail that is.

Passage 3

One of the greatest symbols of the U.S. is the American flag. While cases in the past have defended desecration of the flag as symbolic speech I argue, "Where is the speech in such acts?" I do not believe allowing people to tarnish the flag and thus attack everything that America stands for is the same as allowing free speech. If you have something bad to say about the U.S., say it, but do not cheapen the flag with your actions. Many Americans died to keep that flag flying. Those who want to support flag burning and other such despicable acts are outnumbered.

Last month, 75 people were surveyed in a restaurant in Dallas, Texas, and were asked if they supported the unpatriotic desecration of the American flag in an attempt to express some sort of anti-American idea. Ninety-three percent responded that they were not in favor of desecration of the American flag. Therefore, our national lawmakers should pass a law protecting the American

flag against such horrible actions.

Sample Responses

Passage 1

CONCLUSION: Children of alcoholics are more likely to become alcoholics than are children

of non-alcoholics.

REASON: More alcoholics than non-alcoholics reported a substantially higher rate of

having an alcoholic parent.

Note that the results presented are from one study without reference to how typical these results are. We also do not know where this information was published, so we can make no assessments regarding how rigorously the study was reviewed before publication. However, we can ask some useful questions about the study. The sample size is quite large, but its breadth is questionable. Although multiple states were sampled, to what extent are the people in the AA programs in these states typical of alcoholics across the nation? Also, how do alcoholics in AA compare to alcoholics who have not sought help? Perhaps the most important sampling problem was the lack of a random sample. While the self-reported non-alcoholics were randomly selected in the three states, the respondents in AA were selected on a voluntary basis. Do those who volunteered to talk about their parents differ greatly from those who did not volunteer? If there is a difference between the volunteers and non-volunteers, then the sample is biased.

How accurate are the rating measurements? First, no definition for alcoholic for those answering the survey is given beyond currently being in AA. In addition, we are not told of any criteria given to the research participants for rating parents as alcoholic. Thus we are uncertain of the accuracy of the judgments about whether someone was an alcoholic. Also, problematic is the fact that the selection of the supposed control group of non-alcoholics is based on self-assessment. We know that there is a socially acceptable answer of not being an alcoholic, and people tend to give socially acceptable answers when they are known. This response tendency could also bias the sampling in the supposed control group. We would want to know more about the accuracy of these ratings before we could have much confidence in the conclusion.

Passage 2

CONCLUSION: Three strikes law for criminal offenses are desirable.

REASON: Allowing a criminal to offend three times is like allowing a batter in baseball to swing and miss three times.

The author is arguing the desirability of the three strikes law by drawing an obvious analogy to baseball. The similarity the author is focusing on is that three chances for a batter to hit a ball is much like the three chances awarded to convicted offenders to shape up or to be put in jail for a long time. But simply saying three criminal offenses deserves harsh punishment ignores the complexity involved in criminal sentencing. For example, while a swing and a miss is a strike regardless of the type of pitch the pitcher throws, we might feel context is very important for sentencing criminals. What if the third offense is something very minor? Does it make sense to punish the criminal severely for a third offense regardless of what the other two were? Because of an important relevant difference, we conclude that this analogy is not very relevant.

CRITICAL QUESTION SUMMARY:

WHY THIS QUESTION IS IMPORTANT

When an author offers a reason in support of a conclusion, you want to know why you should believe that reason. By identifying the evidence offered in support of a reason, you are taking another step in evaluating the worth of the reason. If the evidence that supports the reason is good, the reason better supports the conclusion. Thus, you might be more willing to accept the author's conclusion if the author offers good evidence in support of a reason, which in turn provides good support for the conclusion.

0 comments:

Post a Comment