WHAT ARE THE DESCRIPTIVE

ASSUMPTIONS?

You should now be able to identify value assumptions—very important hidden

components of prescriptive arguments. When you find value assumptions, you

know pretty well what a writer or speaker wants the world to be like—what

goals she thinks are most important. But you do not know what she takes for

granted about the nature of the world and the people who inhabit it. Are they

basically lazy or achievement oriented, cooperative or competitive, and rational

or whimsical? Her visible reasoning depends on these ideas, as well as

upon her values. Such unstated ideas are descriptive assumptions, and they

too are essential hidden elements of an argument.

The following brief argument about a car depends on hidden assumptions.

Can you find them?

This car will get you to your destination, whatever it may be. I have driven this

model of car on multiple occasions.

This chapter focuses on the identification of descriptive assumptions.

( j j Critical Question: What are the descriptive assumptions?

Descriptive assumptions are beliefs about the way the world is; prescriptive

or value assumptions, you remember, are beliefs about how the world

should be.

Illustrating Descriptive Assumptions

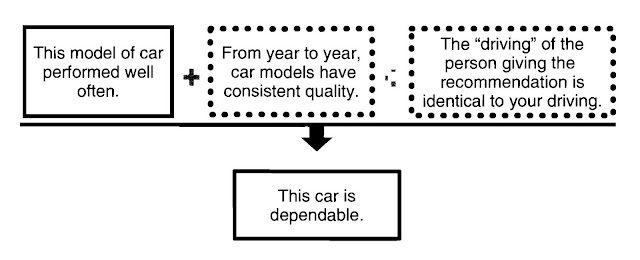

Let's examine our argument about the car to illustrate more clearly what we

mean by a descriptive assumption.

The reasoning structure is:

CONCLUSION: This particular car will get you where you want to go.

REASON: This model of car has functioned well on multiple occasions.

The reasoning thus far is incomplete. We know that, by itself, a reason just

does not have the strength to support a conclusion; the reason must be connected

to the conclusion by certain other (frequently unstated) ideas. These

ideas, if true, justify treating the reason as support for the conclusion. Thus,

whether a reason supports, or is relevant to, a conclusion depends on whether

we can locate unstated ideas that logically connect the reason to the conclusion.

When such unstated ideas are descriptive, we call them descriptive assumptions.

Let us present two such assumptions for the above argument.

ASSUMPTION 1 : From year to year a particular model of car has a consistent quality.

First, no such statement was provided in the argument itself. However, if

the reason is true and if this assumption is true, then the reason provides some

support for the conclusion. But if not all model years have the same level of

dependability (and we know they do not), then experience with a model in previous

years cannot be a reliable guide to whether one should buy the car in the

current model year. Note that this assumption is a statement about the way things

are, not about the way things should be. Thus, it is a descriptive connecting assumption.

ASSUMPTION 2: The driving that would be done with the new car is the same kind driving that was done by the person recommending the car.

When we speak about "driving" a car, the ambiguity of driving can get us into

trouble if we do not clarify the term. If the "driving" of the person recommending

the car refers to regular trips to the grocery store on a quiet suburban street with

no hills, that driving experience is not very relevant as a comparator when the new

car is to be driven in Colorado, while pulling a heavy trailer. Thus, this conclusion

is supported by the reason only if a certain definition of driving is assumed.

We can call this kind of descriptive assumption a definitional assumption

because we have taken for granted one meaning of a term that could have

more than one meaning. Thus, one important kind of descriptive assumption

to look for is a definitional assumption—the taking for granted of one meaning

looks like in argument form:

Once you have identified the connecting assumptions, you have answered

the question, "On what basis can that conclusion be drawn from that reason?"

The next natural step is to ask, "Is there any basis for accepting the assumptions?"

If not, then, for you, the reason fails to provide support for the conclusion. If so,

then the reason provides logical support for the conclusion. Thus, you can say

reasoning is sound when you have identified connecting assumptions and you

have good reason to believe those assumptions.

Attention: A descriptive assumption is an unstated belief about how the

world was, is, or will become.

When you identify assumptions, you identify ideas the communicator

needs to take for granted so that the reason is supportive of the conclusion.

Because writers and speakers frequently are not aware of their own assumptions,

their conscious beliefs may be quite different from the ideas you identify

as implicit assumptions. When you then make the hidden connecting tissue of

an argument visible, you also contribute to their understanding of their own

argument and may thereby guide them to better beliefs and decisions.

USING THIS CRITICAL QUESTION

After you have found descriptive assumptions, you want to think about

whether there is a strong basis for accepting them. It is certainly fair for you

to expect the person making the argument to provide you with some justification

for why you should accept these particular assumptions. Finally, if the

assumption is not supported and you find it questionable, you are behaving

responsibly when you decide not to buy the argument. Your point in rejectingit is not to disagree with the conclusion. Instead, you are saying that you cannot

accept the conclusion based on the reasons offered so far. In other words, you

are quite willing to believe what you are being told, but as a critical thinker you

are in the business of personal development. That development can take place

only when you accept only those conclusions that have persuasive reasons.

Clues for Locating Assumptions

Your task in finding assumptions is to reconstruct the reasoning by filling

in the missing links. You want to provide ideas that help the communicator's

reasoning "make sense." Once you have a picture of the entire argument, both

the visible and the invisible parts, you will be in a much better position to

determine its strengths and weaknesses.

How does one go about finding these important missing links? It requires

hard work, imagination, and creativity. Finding important assumptions is a difficult

task.

You have been introduced to two types of assumptions—value assumptions

and descriptive assumptions. In the previous chapter, we gave you several

hints for finding value assumptions. Here are some clues that will make your

search for descriptive assumptions successful.

Keep thinking about the gap between the conclusion and reasons. Why are you

looking for assumptions in the first place? You are looking because you want to

be able to judge how well the reasons support the conclusions. Thus, look for

what the writer or speaker would have had to take for granted to link the reasons

and conclusion. Keep asking, "How do you get from the reason to the conclusion?"

Ask, "If the reason is true, what else must be true for the conclusion to follow?" And, to

help answer that question, you will find it very helpful to ask, "Supposing the

reason(s) were true, is there any way in which the conclusion nevertheless could be false?"

Searching for the gap will be helpful for finding both value and descriptive

assumptions.

Look for ideas that support reasons. Sometimes a reason is presented with no

explicit support; yet the plausibility of the reason depends on the acceptability

of ideas that have been taken for granted. These ideas are descriptive assumptions.

The following brief argument illustrates such a case:

CONCLUSION: All high-school English classes will go see at least one Shakespeare play.

REASON: It is beneficial to experience Shakespeare's works first hand.

What ideas must be taken for granted for this reason to be acceptable?

We must assume:

(a) The performance will be well done and reflective of what Shakespeare would

encourage, and

(b) students will understand the play and be able to relate it to Shakespeare.

Both (a) and (b) are ideas that have to be taken for granted for the reasons

to be acceptable and, thus, supportive of the conclusion.

Identify with the writer or speaker. Locating someone's assumptions is often

made easier by imagining that you were asked to defend the conclusion. If you

can, crawl into the skin of a person who would reach such a conclusion.

Discover his background. Whether the person whose conclusion you are evaluating

is a corporate executive, a labor leader, a boxing promoter, or a judge,

try to play the role of such a person and plan in your mind what he would be

thinking as he moves toward the conclusion. WTien an executive for a coal

company argues that strip mining does not significantly harm the beauty of

our natural environment, he has probably begun with a belief that strip

mining is beneficial to our nation. Thus, he may assume a definition of beauty

that would be consistent with his arguments, while other definitions of beauty

would lead to a condemnation of strip mining.

Identify with the opposition. If you are unable to locate assumptions by taking

the role of the speaker or writer, try to reverse roles. Ask yourself why anyone

might disagree with the conclusion. What type of reasoning would

prompt someone to disagree with the conclusion you are evaluating? If you

can play the role of a person who would not accept the conclusion, you can

more readily see assumptions in the explicit structure of the argument.

Recognize the potential existence of other means of attaining the advantages

referred to in the reasons. Frequently, a conclusion is supported by reasons

that indicate the various advantages of acting on the author's conclusion.

When there are many ways to reach the same advantages, one important

assumption linking the reasons to the conclusion is that the best way to attain

the advantages is through the one advocated by the communicator.

Let's try this technique with one brief example. Experts disagree about how

a person should establish financial stability. Many times young people are

encouraged to establish credit with a credit card. But aren't there many ways to

establish financial stability? Might not some of these alternatives have less serious

disadvantages than those that could result when a young person spends too much

on that credit card? For example, investing some money in a savings account

or establishing credit by maintaining a checking account are viable routes to

establishing financial stability. Thus, those who suggest that people get credit

cards to help establish financial stability are not taking into account the risks

involved with their solution or the possibility of fewer risks with an alternative.

Avoid stating incompletely established reasons as assumptions. When

you first attempt to locate assumptions you may find yourself locating a stated

reason, thinking that the reason has not been adequately established, and

asserting, "That's only an assumption. You don't know that to be the case." Or

you might simply restate the reason as the assumption. You may have correctly

identified a need on the part of the writer or speaker to better establish the

truth of her reason. While this clarification is an important insight on your part,

you have not identified an assumption in the sense that we have been using it

in these two chapters. You are simply labeling a reason "an assumption."

Here is an example of stating an incompletely established reason as an

assumption.

The ratings are going through the roof for Science Fiction shows. The advertising

agencies have done a great job.

Now, challenge the argument by identifying the following assumption:

The writer is assuming that advertising is causing the ratings to rise.

Do you see that when you do this, all you are doing is stating that the

author's reason is her assumption—when what you are probably really trying to

stress is that the author's reason has not been sufficiendy established by evidence.

Applying the Clues

Let's look at an argument about the importance of planning and see whether

we can identify descriptive and value assumptions.

Planning is a valuable tool. Students need to be taught how to budget time

and write down tasks. The best way to show college students how helpful careful

planning can be for them is to require them to use a planner. Given the average

course load that students take, they will have a difficult time remembering all of

their assignments. Unlike high school, colleges do not have concerned adults

who will remind them about assignments or ask them whether they have done

their homework before they go out.

Requiring the use of a planner will help students become the goal-oriented

students that every college professor wants to have in his classroom. Such a

requirement will not only help students tremendously, but will also create a

more successful college environment for everyone involved.

CONCLUSION Planning should be a requirement for students, and the best way to accomplish

this goal is to require than to use a planner.

REASONS: 1. Students out of high school are not ready or independent enough to for

classes—planning can change that.

2. Students will become goal-oriented.

First, note that the author provides no "proof for her reasons. Thus,

you might be tempted to state, "Those reasons are only assumptions; she does

not know that." Wrong! They are not assumptions! Remember: identifying lessthan-

fully established reasons, though important, is not the same as identifying

assumptions—ideas that are taken for granted as a basic part of the

argument.

Now, let's see whether any descriptive assumptions can be found in the

argument. Remember to keep thinking about the gap between the conclusion

and the reasons as you look. First, ask yourself, "Is there any basis for believing

that the reason(s) might not be true?" Then ask, "Supposing the reason(s)

were true, is there any way in which the conclusion nevertheless could be

false?" Try to play the role of a person who does not believe a planner should

be a requirement.

Look at the two reasons. The first would be true if it were the case

that the students being described are independent learners. This author is

assuming that no such ability to take initiative for one's own academic success

exists. How can she know such a thing? Perhaps forcing students to plan would

only cause the students to have another disorderly thing to do. Thus, one

descriptive assumption is that students cannot learn to become responsible learners

independently.

Let's now suppose that the second reason is true. Planning still might

not be useful to the student. Just because the author believes in the value

of planning does not mean that it will change the lives or the study habits of

students. Thus, an assumption connecting the first reason to the conclusion is

that students will learn how to plan and then will implement that strategy later. This

assumption also links with the second reason closely.

Consider the second reason. It is true only if the student not only

absorbs the ideas of planning, but also uses them. The author is also assuming

that the ideas learned through planning will then lead to a goal-oriented lifestyle. Another important assumption is that students will change their learning

styles after mastering the concepts of planning.

Note also that there is a prescriptive quality to this essay; thus, important

value assumptions underlie the reasoning. What is the author concerned about

preserving? Try reverse role-playing. What would someone who disagreed with

this position care about? What are the disadvantages to forcing students to

plan? Your answers to these questions should lead you to the essay's value preference.

For example, can you see how a preference for orderliness over independence

links the reasons to the conclusion?

Avoiding Analysis of Trivial Assumptions

Writers and speakers take for granted, and should take for granted, certain selfevident

things. You will want to devote your energy to evaluating important

assumptions, so we want to warn you about some potential trivial assumptions.

By trivial, we mean an assumption that is self-evident.

You as a reader or listener can assume that the communicator believes his

reasons are true. You may want to attack the reasons as insufficient, but it is trivial

to point out the writer's or speaker's assumption that the reasons are true.

Another type of trivial assumption concerns the reasoning structure. You

may be tempted to state that the writer believes that the reason and conclusion

are logically related. Right—but trivial. What is important is how they are logically

related. It is also trivial to point out that an argument assumes that we

can understand the logic, that we can understand the terminology, or that we

have the appropriate background knowledge.

Avoid spending time on analyzing trivial assumptions. Your search for

assumptions will be most rewarding when you locate hidden, debatable missing

links.

Assumptions and Your Own Writing and Speaking

When you attempt to communicate with an audience, either by writing or

speaking, you will be making numerous assumptions. Communication requires

them. But, once again out of respect for your audience, you should acknowledge

those assumptions, and, where possible, provide a rationale for why you

are making those particular assumptions.

The logic of this approach on your part is to assist the audience in accepting

your argument. You are being open and fair with them. An audience should

appreciate your willingness to present your argument in its fullness.

Summary

Assumptions are ideas that, if true, enable us to claim that particular reasons

provide support for a conclusion.

Practice Exercises

(J) Critical Question: What are the descriptive assumptions?

For each of the three passages, locate important assumptions made by the author.

Remember first to determine the conclusion and the reasons.

Passage 1

Everyone should consider playing poker to win money. It has gained great popularity.

You can see people play on television daily, and there are many opportunities

to play against real people online. This trend is an exciting opportunity

for people everywhere to try and win money. Poker is simple to learn after one

understands the rules and concepts behind the game. It is a game that people of

all ages and experience can play!

Passage 2

Adopted children should have the right to find out who their biological parents

are. They should be able to find out for personal and health reasons. Most children

would want to know what happened to these people and why they were given

up for adoption. Even though this meeting may not be completely the way the

child had imagined it, this interaction could provide a real sense of closure for

adopted children. There are people who believe that it does not matter who the

biological parents are as long as the child has loving parents. It is true that having

a supportive environment is necessary for children, but there will always be nagging questions for these children that will be left unanswered if they are

not able to find out their biological parents. There are also health risks that

can be avoided by allowing a child to find out who their parents are. A lot of

diseases have hereditary links that would be useful for the child and the new

family to know.

Passage 3

Recently, we have lost community members in a large fire. It only seems logical now

mat we start implementing fire safety presentations or courses in our schools. The

last thing we want to happen is for more tragedies to occur, especially in our schools.

The fire safety training will prevent this community from losing any more lives.

Educational programs provide the best way to go if we are to avoid future disasters

of this type.

Sample Responses

In presenting assumptions for the following arguments, we will list only some

of the assumptions being made—those which we believe are among the most

significant.

Passage 1

CONCLUSION: Everyone should play poker to win money.

REASONS: 1. It is a popular game.

2. People of all ages and experience can play.

In looking at the first reason, there seems to be a missing link between that reason

and the conclusion. The author omits two main assumptions. One, poker is

enjoyable because many people play this game. And second, that "enjoyable"

means profitable. The author needs these two assumptions for him to make the

jump to the idea that we should all join the poker craze.

The second reason should leave the reader wondering whether it makes

sense to assume that because something can happen, it should happen. Yes, we

can all certainly play poker; we can also all start forest fires, but our capacity to

do so is not exactly an endorsement of the activity.

Passage 2

CONCLUSION: Adopted children should be allowed to find their biological parents'

identities.

REASON: 1. Knowing ones birth parents can provide many health benefits (SUPPORTING REASONS)

a. Psychological closure can be achieved by finding answer to enduring

questions.

b. Able to find out what their biological parents are like.

2. Permits one to assess health risks.

Try reverse role-playing, taking the position of someone who values the

parents' right to privacy.

For the first reason to be true, it must be the case that the child is

bothered by not knowing their biological parentage. Surely this assumption

would be true for some adopted children. Is there data that suggests a widespread

burning desire to know the birth parents? If so, please present the data

so we can move toward agreeing with the argument. There are many reasons

to think that the child may either be satisfied not knowing or may not even be

aware that he is adopted. Also, for the main reason to be enhanced by the

supporting reasons, we would need to assume that meeting the biological

parent would not create sharp new tensions between the individual and the

adoptive parent.

ff\ CRITICAL QUESTION SUMMARY:

Vjt^ WHY THIS QUESTION IS IMPORTANT

What Are the Descriptive Assumptions?

When you identify descriptive assumptions, you are identifying the link between

a reason and the author's conclusion. If this link is flawed, the reason does not necessarily

lead to the conclusion. Consequently, identifying the descriptive assumptions

allows you to determine whether an author's reasons lead to a conclusion.

You will want to accept a conclusion only when there are good reasons that lead

to the conclusion. Thus, when you determine that the link between the reasons

and conclusion is flawed, you will want to be reluctant to accept the author's

conclusion.

0 comments:

Post a Comment